I’m going to make an uncomfortable prediction about your business.

The acquisition channel your team is most excited about (the one with the best CAC, the one you’re scaling spend on) is probably your worst channel by customer lifetime value.

And that welcome offer driving all those conversions? It’s likely training customers to never pay full price again.

I’ve seen this pattern destroy margins at fashion brands doing $5M, $20M, even $50M in revenue. The math looks great on the dashboard. The bank account tells a different story.

The LTV Lie Most Apparel Brands Tell Themselves

Here’s how the conversation usually goes:

“Our LTV is $180, our CAC is $45, so we’re at a 4:1 ratio. We can scale.”

Sounds healthy. But when I ask how they calculated that $180, it’s almost always revenue over 12 months.

Not contribution margin. Revenue.

In apparel, that’s a dangerous number to scale against. Here’s why:

COGS eats 35-50% of that revenue (fabric, manufacturing, duties, freight).

Variable costs take another 15-25% (shipping both ways, payment fees, pick-and-pack, packaging).

Returns (fashion has 20-30% return rates) don’t just reduce revenue. They add cost. A returned $100 dress can cost you $15-20 in shipping alone, plus the lost margin.

Discounts which most fashion brands use heavily—shrink margin further.

That $180 “LTV” often becomes $50-70 in actual contribution margin.

Suddenly that 4:1 ratio is actually 1.3:1. You’re not scaling profitably. You’re buying revenue at a loss and hoping retention will save you.

The Only LTV Formula That Matters

Real LTV for a DTC apparel brand:

This is the money that actually pays for your fixed costs, your team, your growth. Everything else is vanity.

My strong opinion: if you’re not calculating LTV this way, you don’t actually know your unit economics. You’re guessing.

Three Patterns I See Repeatedly

These aren’t hypotheticals. These are patterns I’ve seen across dozens of fashion and apparel brands.

Pattern 1: The TikTok Trap

A women’s fashion brand, around $12M in revenue. Their growth team was ecstatic about TikTok. CAC of $28 versus $52 on Meta. They shifted 40% of budget to TikTok over six months.

When they finally ran the cohort analysis by channel:

TikTok customers had 35% higher return rates

Second purchase rate was 11% (versus 24% from Meta)

12-month contribution margin LTV: $34 (versus $89 from Meta)

The “cheap” channel was actually 2.6x more expensive on a true LTV:CAC basis. They’d spent six months scaling in the wrong direction.

Pattern 2: The Discount Death Spiral

An activewear brand, $8M revenue. They’d always used 20% off welcome offers. Conversion rates were solid. Growth was steady.

But when they segmented LTV by first-order discount:

Customers acquired at 20% off had 12-month LTV of $52

Customers acquired with free shipping (no discount) had LTV of $78

Full-price first purchasers had LTV of $112

The 20% offer wasn’t just costing them margin on the first order. It was attracting customers who waited for sales and had 2x higher return rates. They were training their customer base to be unprofitable.

The fix wasn’t complicated: they tested a “free shipping + free returns” offer instead. Conversion dropped 15%, but LTV:CAC improved by 40%.

Pattern 3: The Hero Product Mismatch

A men’s basics brand, $15M revenue. Their acquisition creative featured their bestselling t-shirt, highest volume, good margin, great reviews.

But when they analyzed LTV by first product purchased:

T-shirt first buyers: 18% repeat rate, $61 LTV

Underwear first buyers: 34% repeat rate, $118 LTV

Sock subscription first buyers: 52% repeat rate, $187 LTV

They’d been optimizing acquisition for the wrong product. The t-shirt brought volume but terrible retention. The “boring” subscription offering created customers worth 3x more.

Your hero product for acquisition might not be your hero product for lifetime value.

Why This Matters More in 2026

Three years ago, you could get away with sloppy LTV math. Capital was cheap. CACs were lower. Growth forgave a lot of sins.

That’s over. Here’s what’s changed:

CACs have doubled or tripled on most paid channels since iOS 14. The margin for error on acquisition is gone.

Capital is expensive. If your payback period is 12+ months, you need a lot of runway and investors are scrutinizing unit economics harder than ever.

Shipping and fulfillment costs keep rising. Free shipping + free returns is table stakes for fashion customers, but someone has to pay for it.

Return rates are climbing. Bracket shopping is normalized. Some brands see 30%+ return rates on certain categories.

The brands that will survive this environment are the ones who know with precision; which customers, channels, products, and offers actually make money. Not revenue. Money.

The Monday Morning Framework

Here’s what I’d do if I took over retention and growth at an apparel brand tomorrow:

Step 1: Fix the Formula (Week 1)

Stop using revenue-based LTV immediately. Build a contribution margin model that includes COGS, variable fulfillment, payment processing, discounts, and the full cost of returns (shipping both ways + restocking + unsellable inventory).

Pick a time window. For most fashion brands, 12 months is the right starting point. You can also track 6-month and 24-month for comparison, but 12 is your primary metric.

Step 2: Segment Everything (Week 2-3)

Calculate LTV separately for:

Acquisition channel : Meta vs TikTok vs Google vs organic vs email

First product purchased : which entry points create the best customers?

Welcome offer : 10% off vs 20% off vs free shipping vs full price

Geography : domestic vs international, by region

Cohort month : are recent customers behaving differently than older ones?

You’re looking for asymmetry. Somewhere in your data is a segment that’s dramatically better or worse than average. Find it.

Step 3: Set Your Ceiling (Week 4)

For each segment, calculate the maximum CAC you can afford:

Conservative (3:1 ratio): Divide LTV by 3

Moderate (2.5:1 ratio): Divide LTV by 2.5

Aggressive (2:1 ratio): Divide LTV by 2 (only if you have capital runway)

This becomes your ceiling, not your target. If a channel can’t acquire customers below that ceiling profitably, it’s not a scale channel, it’s a brand awareness channel at best.

Step 4: Kill and Scale (Ongoing)

Kill: Acquisition sources, products, and offers with LTV:CAC below 2:1. No exceptions. No “but it drives volume” arguments. Volume at a loss is not a strategy.

Scale: Double down on segments with LTV:CAC above 3:1. Shift budget aggressively. Test expanding those segments—can you find more of those customers? Can you move them through different creative or channels?

Optimize: For segments between 2:1 and 3:1, focus on improving retention. Post-purchase flows, better onboarding, loyalty mechanics. These are your swing segments.

What I’d Stop Doing Immediately

A few unpopular opinions:

Stop celebrating low CAC without checking LTV. A $20 CAC on a $30 LTV customer is worse than a $60 CAC on a $200 LTV customer. Do the math.

Stop using percentage-off welcome offers by default. Test free shipping, free gift with purchase, or even no offer. The customers you lose might be the ones you didn’t want anyway.

Stop optimizing for blended metrics. Blended CAC and blended LTV hide the truth. The average of a great segment and a terrible segment looks mediocre. But the fix isn’t incremental improvement, it’s cutting the terrible segment entirely.

Stop investing in retention after month 5. Data shows fashion LTV curves flatten around month 5. If you haven’t captured a repeat purchase by then, you probably won’t. Front-load your retention efforts to months 1-4.

Stop treating returns as a revenue problem. Returns are a margin problem, a logistics problem, and often a product or sizing problem. If certain SKUs have 40% return rates, the issue isn’t customer behavior, it’s your product page, fit guide, or the product itself.

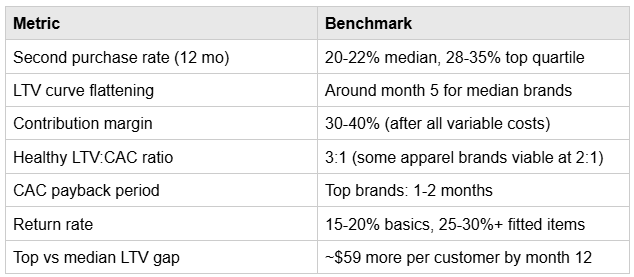

Benchmarks Worth Knowing

For apparel and fashion DTC:

Metric

Benchmark

The Bottom Line

LTV isn’t a mystical number. It’s a calculation but only if you calculate it correctly.

For apparel brands, that means contribution margin, not revenue. It means accounting for the real cost of returns, shipping, and discounts. And it means segmenting ruthlessly until you find where your best and worst unit economics live.

When you get this right, LTV stops being a number you report to investors and becomes a map. A map that tells you which channels to scale, which products to lead with, which offers to kill, and which customers to fight for.

The brands winning right now aren’t the ones with the lowest CAC or the highest revenue. They’re the ones who know exactly which customers make them money and they’re relentless about finding more of them.

Your LTV is probably wrong. It’s based on revenue, not contribution margin.

When you fix the formula and segment the data, you’ll likely discover that your best CAC channel has your worst LTV and your boring, lower-volume channels are actually driving profitability.

Fix the math first. Then scale what actually works.